After the horrifying Pearl Harbor attack by Japan, many Americans were distrusting of all Japanese-Americans living in the U.S. The government ordered around 110,000 Japanese-Americans into internment camps.

The Federal government classified all Japanese-American men of draft age, except those already in the armed forces, as 4-C, enemy aliens, who were forbidden to serve the U.S. Military.

Private Tsuneo Shiroma, of the 522nd Field Artillery Battery B, in a foxhole during the Allied invasion of Italy. 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Meanwhile the Japanese government had been making propaganda in Asia out of the internment of Japanese-Americans. The camps appeared to confirm their depiction of the war as a racial conflict. The effective propaganda forced Washington to reverse its policy on military service in early 1943.

In response to the Japanese propaganda, and under pressure from civil liberties organizations, President Roosevelt authorized the enlistment of Japanese-American men into the U.S. Armed Forces.

This permitted Japanese Americans to form a special infantry outfit called the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team. In Hawaii alone, recruitment exceeded all expectations. When the Army called for 1,500 volunteers, 10,000 turned up at recruiting offices.

Soldiers of the 442nd salute the flag at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. June, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Not all were eager to serve a government that had forced their families into internment camps. Some refused to cooperate with the draft until their rights were restored.

Many military leaders also were reluctant to have Japanese Americans in the military. Even General Eisenhower’s staff rejected the idea of Japanese-American troops. But General Mark Clark, commander of the Fifth Army in Italy, had said that he would “take anybody that will fight”.

So in June 1944, the 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team was deployed in Italy to prove themselves, fighting alongside the 100th Infantry Battalion, the battle-tested unit made up mostly of Japanese Americans from Hawaii.

Before the ban had been placed on the enlistment of Japanese Americans, the 100th had been formed in 1942 in which they had seen action in North Africa and Italy. For months, the men of the 100th had distinguished themselves in repeated assaults on the German lines as the Allies fought northward in Italy. The 100th had lost over 950 men, so many that they came to be called the “Purple Heart Battalion.”

The fall of Rome in June 1944 boosted Allied forces’ morale. But it had not ended warfare in Italy. New troops were needed to fight the Germans. As the campaign in Italy continued into the autumn, the newcomers of the 442nd and the combat-wise survivors of the 100th would be asked to spearhead the Fifth Army’s drive northward from Rome.

1943

Photo credit: Library of Congress

The 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team fought so well and so hard in the drive toward the German “Gothic Line”. General Clark was so impressed that when he led his men into the city of Livorno in full view of cameras that accompanied him everywhere, the General insisted that the Japanese Americans march right behind his jeep.

“They were superb! They showed rare courage and tremendous fighting spirit. Everybody wanted them”, said General George Marshall.

The 442nd was then rushed to the battlefields of France. Once unwanted and considered a “problem” by the U.S. army, the 442nd was now seen as a problem solver.

But during these battles they would endure in the Vosges Mountains in France. This was their greatest challenge. During this time, they were under the command of an incompetent General who would send them into impossible situations where they would endure terrible losses.

On October 29, 1944, the 442nd was ordered to rescue the so-called “Lost Battalion” – 275 men from the 141st Regiment who had been surrounded by Germans due to the reckless orders of their General.

During the rescue, the 442nd lost 400 men but they had successfully rescued 230 men of the Lost Battalion. This further secured their reputation for extraordinary bravery and valor.

At the end of the war, the “Purple Heart Battalion” suffered 9,486 casualties. Over 600 of them made the ultimate sacrifice.

The Japanese Americans would then again called upon to help win the war in the Pacific. They mostly worked as interpreters and translators in the war against Japan. Many served in the Military Intelligence Service, intercepting secret Japanese communication, often making quick translations of the battlefield messages and orders of Japanese officers.

In Okinawa and Saipan, they were able to convince some Japanese soldiers to surrender. They tried to reason with terrified civilians who had been told by the Japanese to expect horrible atrocities at the hands of the arriving Americans.

The bravery and sacrifice of Japanese-American soldiers would be later recognized. After 55 years, 20 members of the 442nd would finally be awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor.

Nobody could ever again doubt the Japanese Americans’ loyalty and their incredible courage and contributions to winning the war.

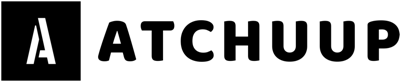

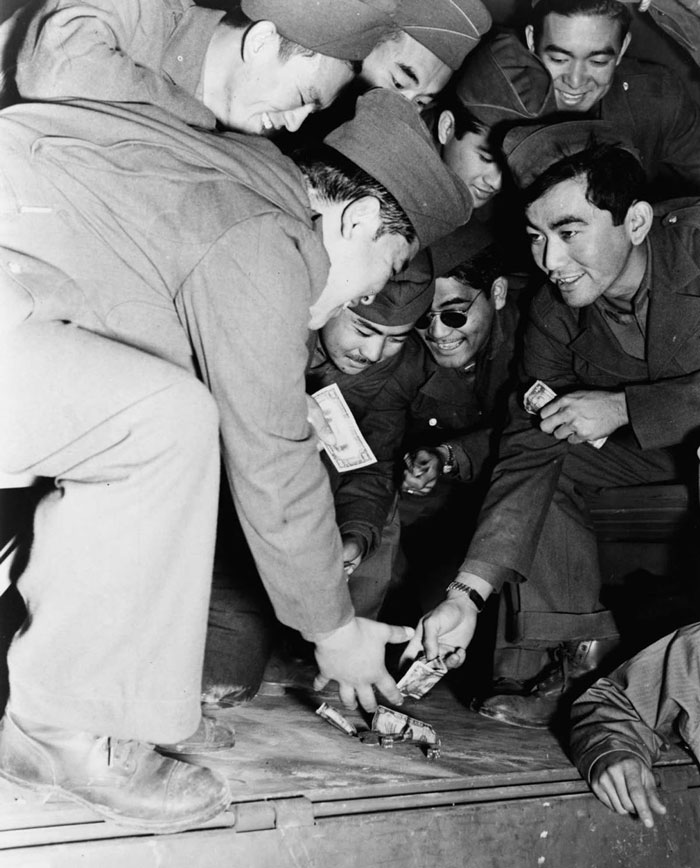

Soldiers distribute candies and cigarettes donated by a Hawaiian pineapple company. 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers receive training on heavy weaponry. 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers of the 442nd train in building and attacking across a pontoon bridge. July, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers enjoy ukulele music while awaiting orders. 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Private Jack Y. Oato purchases $2,500 worth of war bonds from his company commander. June, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

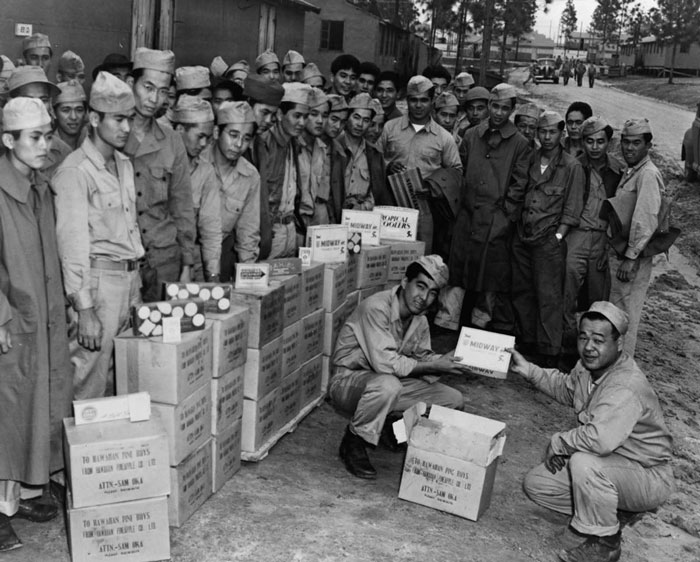

Private Harry Hamada does a hula dance with musical accompaniment. June, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

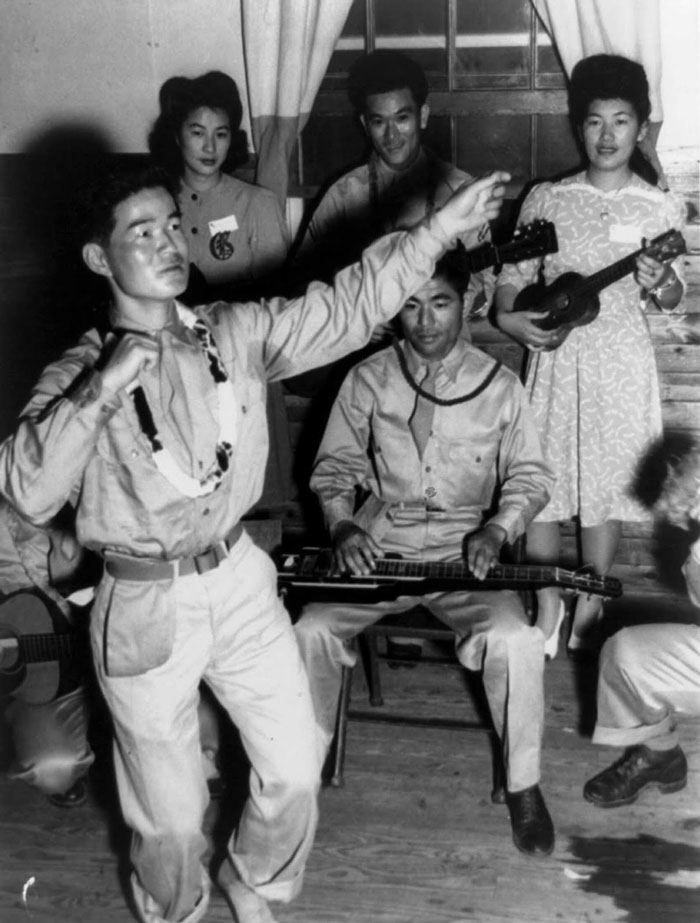

Soldiers of the 442nd dance with Japanese-American women from Jerome and Rohwer Relocation Center at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

1943

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers of the 442nd kill time at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. June, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Members of the 442nd on the march in the Chambois Sector, France. 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Shiro Yamato and Ginchi Masumotoya wash their uniforms in their helmets behind the lines during the invasion of Italy. October, 1943.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

A unit of the 442nd on the front lines near St. Die, France. Nov. 13, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

A soldier of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team mans a post near St. Die, France, armed with an antitank rocket launcher. Nov. 17, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers launch mortars at German snipers in Italy. Aug. 25, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldier drive a Jeep towing a supply trailer in rural France. October 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers fire 105mm shells at German positions to support an infantry attack in France. Oct. 18, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers fire mortar shells at German troops in France. Oct. 1, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers of the 442nd dash for cover during a German artillery attack in Italy. April 4, 1945.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Soldiers man a machine gun nest in eastern France. Sept. 1, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

A soldier of the 442nd cleans the barrel of an 81mm mortar near St. Die, France. Nov. 17, 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

A squad leader of the 442nd watches for German troops in France. November 1944.

Photo credit: Library of Congress